Welcome to the second portion of restaurant capital and ownership series: How Distributions and Profit and Loss Allocations are Taxed! In Part I, Raising and Distributing Capital for Restaurant Startups, we discussed what capital is, how to read an operating agreement, and we walked through an example showing how capital is distributed among owners. In Part II, we’ll cover how distributions and profit and loss allocations are taxed. First, let’s cover some basics of partnership taxation.

How the Tax Forms Flow

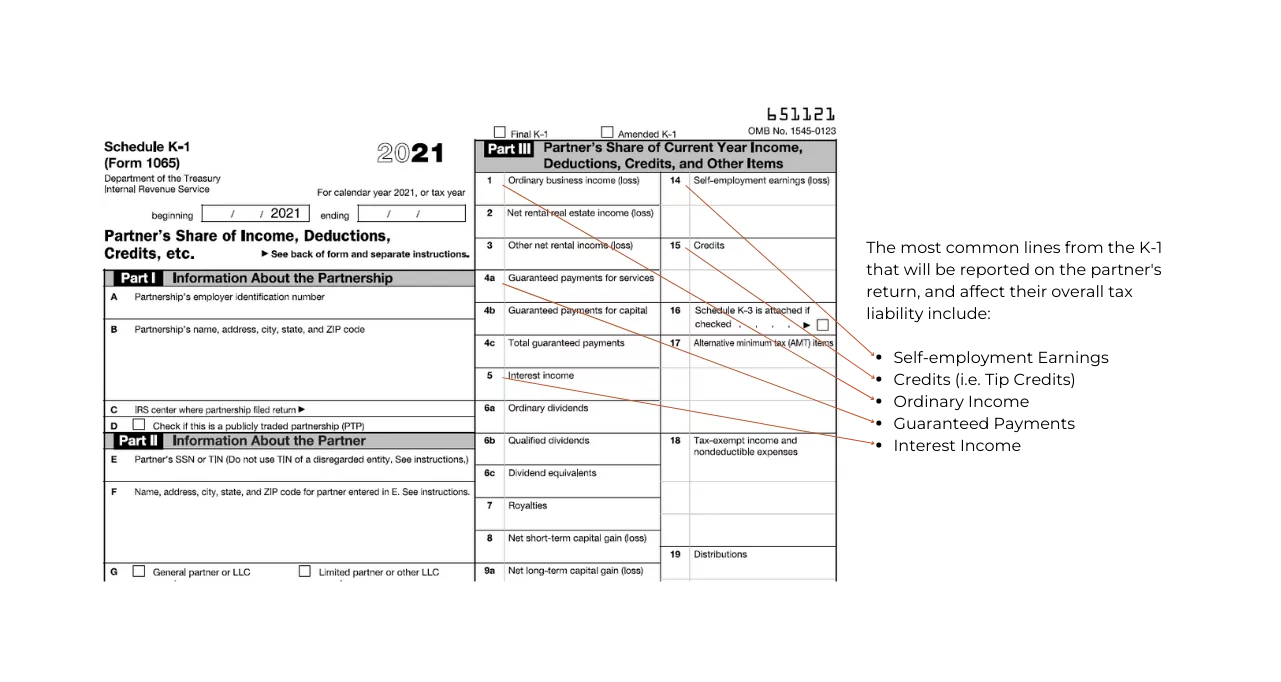

The Partnership entity (or their accountant) is responsible for filing Form 1065 – Partnership Income Tax Return, which includes From K-1. After filing, the K-1 is distributed to each partner, with that partner’s specific information about their investment. The K-1 describes how the distributions and profit and loss allocations flow to each partner.

Each partner will use their Form K-1 to report the applicable information on their personal tax return. Each partner is responsible for their portion of income and losses to be reported to the IRS.

What is on Form K-1?

There are 3 sections on Form K-1 reporting to each partner information about their investment:[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Section of K-1

Items Reported

How Reported Info is Used

Part I: Information About the Partnership

- Partnership’s EIN

- Name

- Address

Used to identify to the IRS what entity the partner is reporting information regarding

Part II: Information About the Partnership

- Partnership’s EIN

- Name

- Address

Used to identify to the IRS what entity the partner is reporting information regarding

Part III: Information About the Partner

- Partner’s SSN or EIN

- Name

- Address

- type of ownership

- Partner’s share of profit, loss, and capital by percentage

- Partner’s share of liabilities

- Partner’s Capital Account Analysis

Used to report to the IRS the partner’s information.

Used by the partner to see their investment in the partnership.

Gives each partner information about their investment, and the balance of their investment.

What does a K-1 look like?

These amounts allocated to the partner on the Form K-1 will be added to their other income/losses from various sources for the year to calculate their personal income tax liability.

Taxes on Distributions

How are capital distributions taxed? The simplest answer is that they are not! Distributions are not taxed when paid out to the partners, and are reported on the K-1 Part II “Partner’s Capital Account Analysis” as described above. The Part II capital account section tracks each partner’s capital account individually. You can think of it like a hypothetical savings account with the restaurant – because savings accounts are not taxed. This capital account will generally increase with capital contributions and the allocation of profits, and decrease with capital distributions and the allocation of losses. The increases and decreases to your K-1 Part II capital account do not flow through to be reflected on the partner’s personal return and thus, are not taxable. Note that whether or not the distribution of cash from the partnership is discretionary or is derived from the estimated amount of the entity’s taxable income that will flow through to you, that distribution itself is not taxable. These “tax” distributions are intended to give each partner enough cash to cover their personal tax obligation (as a result of the entity’s income that flows-through) when they pay quarterly estimated tax payments throughout the year, or pay the final tax liability when the tax return is filed. As we discussed in the previous blog, distributions can be paid out in various ways, as described by the operating agreement in place.

Tax on Flow-Through Profit and Loss Allocation

When we say the profits and losses of the restaurant “flow-through” to the partner’s return, we mean that the partnership itself is not taxed on the profit and losses; however, each partner is taxed on their share of the profit and losses as allocated. Unlike distributions, the increase and decrease to your capital account by the profit and loss allocation is taxable. It is worth mentioning that changes to the capital account and the profit and loss allocations do not have to relate to each other on when they take place. The profit and loss allocation is set up for each year and is reported annually through tax returns, but distributions are generally discretionary based on the operating agreement. Here is a capital distribution example from our previous post:

(b) Periodic Distributions of Cash Available for Distribution. Subject at all times to the Company’s current and future capital needs and its liquidity, including the availability of current cash flow, which shall be determined by the Board in its sole discretion, and subject to Section 7.01(d), the Board may from time to tome cause the Company to make such distributions of Cash Available for Distribution as the Board may determine.

As you can see, the distributions in this example are determined by the Board, depending on cash available from the restaurant. Occasionally, a timing issue arises when a tax liability is created via profit allocated on the K-1, but the partnership does not distribute cash. In the financial world, this is called “phantom income”.

Phantom Income

Phantom income is income that the partners are allocated, and taxed on their personal returns, but which they never physically receive as income in their pocket. To explain using the Basics above, the allocation of profits and losses shown on Form K-1, Part III are amounts reporting that partner’s share of the partnership financial activity for that year. It does not guarantee that any amount of cash was given to that partner, nor does it guarantee that any cash distribution that the partner did receive matches the allocation of profit or loss. This phantom income can create cash flow complications for partners if they must pay tax on income that was never actually paid out. The partner can see via the K-1 that the capital account increased, and they now hold more value, but the partner has yet to receive the income in a distribution that they can use to pay the tax. Phantom income is especially prevalent in start-up years when distributions are usually held back to reinvest and grow the business, making it a disadvantage to new investors during those critical years.

How to Determine Profit and Loss Allocations

Just like determining how the distributions are paid to each partner, we must look at the operating agreement to determine how profits and losses are allocated. Some operating agreements mimic the “tiers” of distributions for allocations for profit and losses. Other operating agreements have allocations based on partnership percentage.

Ultimately, the goal of tax profit and loss allocations is to follow the true economics of the deal, which is usually represented in the distribution clause of the operating agreement. For example, if a restaurant generates $500K in profit and the investors are entitled to 50% of those profits, their K-1 will show $250K of taxable profit allocated to them regardless of how much cash is actually distributed to them. It’s easier to understand this disconnect between distributions and profit/loss allocations by thinking of this in terms of hypothetical liquidation. Assume the partnership started with zero assets and were to liquidate at the end of the year after generating $500k in profits, and the operating agreement states that the investors are owed 50% of profits, then they would receive $250K in cash upon liquidation. That is why they are taxed on this money regardless of whether it is distributed or not.

Distribution and Profit and Loss Allocation Example

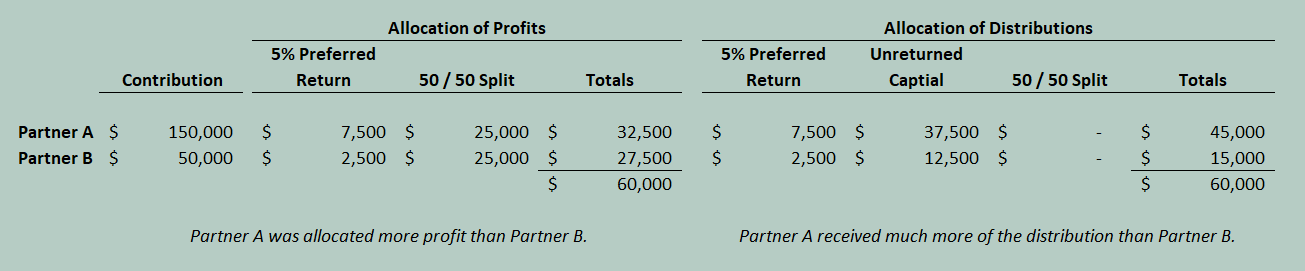

This example shows you how distributions and profit and loss allocations do not always match up, even though they are related, and shows you what will be taxable to the partner.

- Partner A contributes $150,000 to the company

- Partner B contributes $50,000 to the company

Per the operating agreement, allocations of profits and losses are allocated to each partner first to the extent of 5% cumulative annual preferred return on unreturned capital and second 50% to A and 50% to B. Cash is first disbursed to pay the preferred return, second to pay any unreturned capital and last 50% to A and 50% to B.

Whew! That’s a mouthful, right? Let’s break it down.

First: Profit and Loss Allocations

- 5% cumulative annual preferred return on unreturned capital. As stated in the first blog of this series, the unreturned capital is the amount the partner contributed less prior distributions. For example, if the partner contributed $150K and received distributions of $50K, the unreturned capital balance would be $100K. Most likely, this is included in the operating agreement so that Partner A can get a return on their investment faster since they contributed more money to start.

- 50/50 Split of the remainder of profits

Second: Distributions

- Preferred return. This is the same amount as the 5% from step one of the allocation of profits and losses.

- Unreturned Capital. This is the remaining amount of capital the partner contributed but has not yet been paid back through distributions

- 50/50 Split of any remaining cash distribution

Let’s say that in Year 1, the partnership has $60K in profit (taxable income) and pays out $60K in distributions. Here’s how it would look:

Even though in Year 1, the Partnership distributed the same amount in cash as was earned in profit, the allocations to those partners are different because of the operating agreement.

It is often set up that the partners that invested more money get their return on their investment quicker. This creates the incentive to invest more and take on more risk.

In this case, Partner B is allocated $27,500 of taxable income. However, Partner B only receives $15,000 of cash distribution. It’s the opposite for Partner A, who received more cash than allocated taxable income. Some might not think this is “fair”, however, we must follow the operating agreements for each partnership. As the years pass, the allocation between Partner A and Partner B will become closer as the unreturned capital diminishes, and ultimately the overall allocation and distribution will become 50/50 split between the partnership.

Remember, the Allocation of Profits will be shown on Part III of the K-1 to each partner. That partner is responsible for reporting that income as part of their personal tax return. The Distribution will be reported on Part II of the K-1. This is not taxable. It will only show that their capital account decreased.

Partner B – Part II, Form K-1, Capital Account Analysis

This section is informational, showing the partner their balance in the partnership:

This is taxable income to the partner:

We hope this gives you an understanding of partnership distributions and profit and loss allocations, and the related tax consequences. These are some complex tax issues, and because a restaurateur’s time is valuable and limited, partnering with a CPA firm that specializes in handling restaurant accounting is vital. At The Fork CPAs, we are ready to assist you with your restaurant accounting needs. Feel free to reach out and set up a discovery call.